2022.06.03

EXHIBITION 09

NAOKI ISHIKAWA

“THE VOID”and wander journal #48

北極圏やヒマラヤ山脈といった辺境から、日本の来訪神や先史時代の洞窟壁画まで。自らの身体で世界を知覚し、それを写真に収めてきた石川直樹さん。そんな石川さんの“写真家としての出発点”と言えるのが、2005年に発表された写真集『THE VOID』です。被写体は、ニュージーランドの先住民マオリが聖地として受け継いできた原生林。そこでは、自然と人間が成熟した関係性を築いていました。地球環境への関心が高まる今、石川さんの写真と言葉は、私たちに多くの気づきを与えてくれます。地球の未来を考えるために――。東京の一角で、マオリの森を感じてみてください。

and wander OUTDOOR GALLERY with PAPERSKY

2022年6月3日(金)〜7月31日(日)

12:00 – 19:00 (最終日は17:00までとなります) 木曜定休

東京都渋谷区元代々木町22-8 3F, 4F

tel. 03-6407-8179

and wander 丸の内

2022年6月3日(金)〜6月30日(木)

11:00 – 20:00 会期中無休

東京都千代田区丸の内3-3-1 新東京ビル1F

tel. 03-6810-0078

From remote frontiers such as the Artic or the Himalayas, to Japanese raiho-jin (visiting deities) or prehistoric cave paintings, Naoki Ishikawa uses his photography to capture the world as he physically perceives it. His 2005 collection “THE VOID” could be considered the starting point for Ishikawa’s journey as a photographer. The sacred virgin forests of the Maori, the indigenous people of mainland New Zealand, were the subject of the collection. These forests are a place where nature and humans have established a mature relationship. In today’s era of heightened interest in environmental issues, Ishikawa’s photographs and words make us aware of many new things. We invite you to this little corner of Tokyo to immerse yourself in the forests of the Maori and to contemplate the future of the planet.

and wander OUTDOOR GALLERY with PAPERSKY

3 June ~ 31 July, 2022

12:00 - 19:00 (closes at 17:00 on the final day) closed on Thursdays

3F,4F, 22-8 Motoyoyogicho, Shibuya, Tokyo

tel. 03-6407-8179

and wander Marunouchi

3 June ~ 30 June, 2022

11:00 - 20:00

1F, Shin-Tokyo Bldg. 3-3-1 Marunochi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo

tel. 03-6810-0078

INTERVIEW

『THE VOID』は写真家の石川直樹さんが2005年に発表した写真集です。そこに写るのは、ニュージーランド・北島に広がる原生林。先住民マオリが聖地として受け継いできた鬱蒼とした深い森です。若き石川さんはその森をひとり歩き、1ヶ月半かけて、目に留まった風景を撮影し続けました。17年前の作品を眺めながら「この時に考えていたことと今思うことは、何ら変わっていない」と話す石川さん。マオリの森で感じたことを、改めて聞きました。

INTERVIEW

“THE VOID” is a collection of photographs by Naoki Ishikawa that he published in 2005. The photographs depict the virgin forests of New Zealand’s North Island — rich, dense forests that are sacred to the indigenous Maori people. A young Ishikawa trekked solo through these forests for a month and a half, taking pictures of what he saw as he went. “My thoughts at the time are no different from what I think now” comments Ishikawa, as he looks back over his work from 17 years ago. We took this opportunity to ask him to recall his experience of the Maori forests.

2005年に発表された『THE VOID』(ニーハイメディアジャパン)。「自分としてはこれが写真家としてのデビュー写真集だと思っています」と石川さん。1ヶ月半におよぶ滞在で撮った膨大な写真から31点を厳選し、写真家として世界を見る眼差しを明確にした。

“THE VOID” (2005, Knee High Media Japan). “This was my debut collection as a photographer” says Ishikawa. Through the process of painstakingly selecting just 31 images from the vast collection he shot during his six-week stay, Ishikawa clarified his photographic eye for the world.

17年の時を経て、再び多くの人の目に触れることになった「THE VOID」シリーズ。展示は東京・元代々木町にあるOUTDOOR GALLERY with PAPERSKYとand wander 丸の内の2会場で開催される。写真はOUTDOOR GALLERYの様子。

After 17 years, the "THE VOID” Ishikawa’s first full book of photography has been re-launched and is once again on exhibition. The exhibition is currently being held at two venues: OUTDOOR GALLERY with PAPERSKY in Moto-Yoyogi-cho, Tokyo. And at and wander Marunouchi also in Tokyo.

ニュージーランドの北島は“カヌーの生まれる場所”。

――ニュージーランドの原生林を撮ろうと思ったきっかけを教えてください。

きっかけは、星を見ながら海を渡る伝統航海術「スターナビゲーション」への関心でした。学生時代からミクロネシアのサタワル島などに行き、現地の人々から航海術を学ぼうとフィールドワークを続けてきました。こうした旅の目的地は、やがてミクロネシアからポリネシアへと広がっていきました。ハワイ、イースター島、ニュージーランドを繋いだ三角形の地域を「ポリネシアトライアングル」と呼ぶのですが、ヨーロッパの3倍程ある広大なエリアにも関わらず、言語や風習でひとつの文化圏を成しています。それは、古来の人々が伝統航海術によって島々を行き来してきたからにほかなりません。そして、その航海に使うカヌーの原材料となった巨木がニュージーランドの北島にあると聞き、「カヌーが生まれる場所を見てみたい」と思ったんです。

New Zealand’s North Island is where “canoes are born”.

――Could you tell us about what inspired you to photograph New Zealand’s virgin forests?

The initial impetus was my interest in “star navigation”, a traditional navigation technique that uses the stars to navigate the oceans. When I was a student, I travelled to Satawal Island in Micronesia and conducted fieldwork to learn navigational techniques from the local people. From there, my travels eventually took me from Micronesia to Polynesia. The triangular area between Hawaii, Easter Island and New Zealand is referred to as the “Polynesian Triangle”. Despite covering an expansive area, approximately three times the size of Europe, the area constitutes a single cultural region in terms of language and customs. It was none other than the traditional navigation techniques that enabled ancient people to travel between these islands, that made this cultural unity possible. When I heard that the giant trees that were used to make the canoes for these ocean crossings could be found on New Zealand’s North Island, I thought “I want to see the place where canoes are born”.

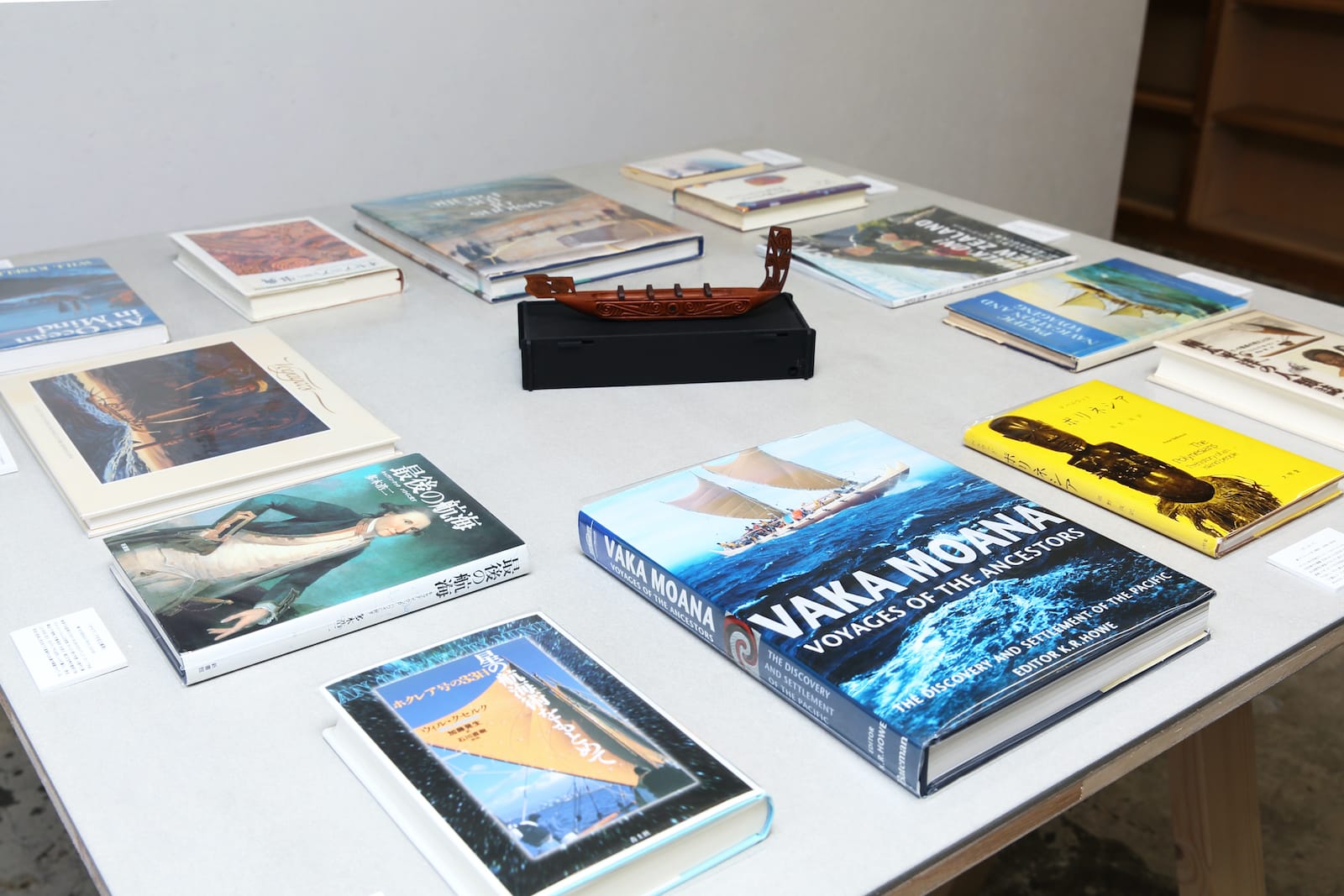

スターナビゲーションは星だけでなく、太陽や風、海鳥の飛ぶ方角やその時々の海の色など、自然をすべて使って航海をする高度な技術。コンパスなどは一切使わないが、GPSにも劣らない精度で、海上の自分の居場所を導き出すという。会場では、石川さんからお借りした、スターナビゲーションを用いた航海術やポリネシア文化に関する書籍も閲覧できる。

Star navigation is an ancient technology in which seafarers use only the stars to navigate themselves across extremely long distances. In addition to the stars, the sun, wind, sight of birds, currents and the color of the sea are all incorporated into this extremely accurate pre GPS system of navigating. We have gathered a few books from Naoki Ishikawa’s collection for you to browse and learn more about the Polynesian culture and star Navigation.

――森に入った時の印象は覚えていますか?

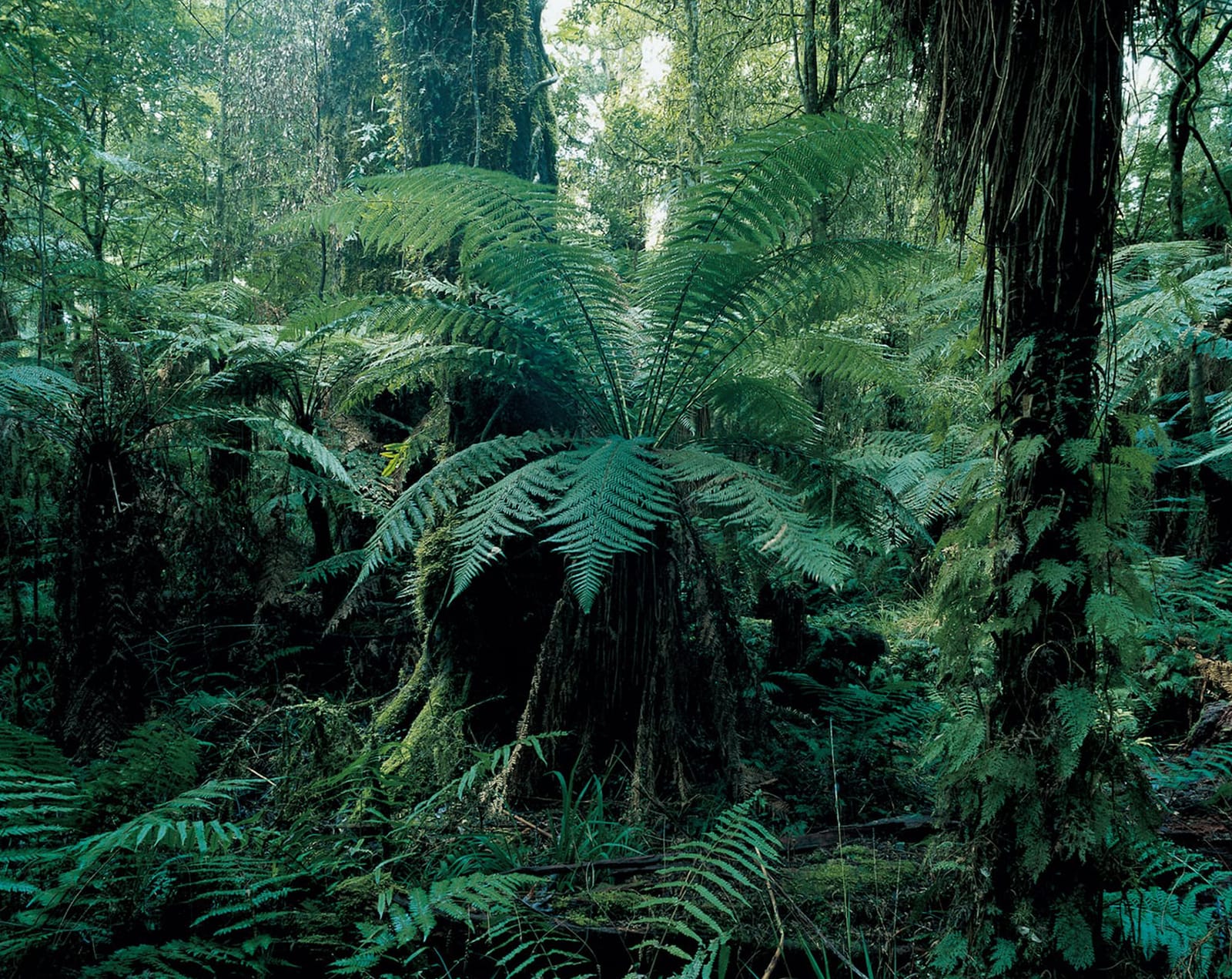

当時は北極や南極、エベレストには行っていましたが、森に長く滞在する経験はなかったので、“見たことのない場所”という印象を受けました。日本なら屋久島に近いけれど、人の痕跡がより薄い。木道のトレイルなどはそこまで整備なくて、今にも植物に覆われてしまいそうな細い轍が続いている。そこをひたすら歩いたり、一箇所に留まったりしながら、1ヶ月半くらい過ごしました。人を襲うような猛獣がいないので、その点はリラックスできました。飛べない鳥のキウイとか、大きなカタツムリなどがたくさんいて、生き物の気配はあちこちから感じる。動物は飛び出してこないけれど、突如として巨大な木が現れたり。湿度もあって、雨もそうとう降っていた記憶があります。

――Do you remember your first impression when you entered the forest?

At the time, although I had been to both the Arctic and Antarctica as well as Mt. Everest, I had never experienced staying in a forest for an extended period of time, so my first impression was: “this is a place that I have never seen before”. If I were to compare it to somewhere in Japan, I would say it is similar to Yakushima, but traces of humans are even sparser. Wooden boardwalks were few and far between. Instead there were narrow tracks that looked like they were just about to be completely covered up by vegetation. I spent about a month and a half just walking along these trails, sometimes stopping in one place. There were no predators that would attack humans, so that was something that I could relax about. I could sense the presence of living beings all around me, such as the flightless bird, the Kiwi, or giant snails. Animals did not jump out at me, but sometimes an enormous tree would just appear right in front of me. It was humid and I remember that it rained a lot too.

ニュージーランド・北島に広がる原生林。若き日の石川さんはここにひとりで1ヶ月半ほど滞在し、撮影を行った。©︎NAOKI ISHIKAWA

Virgin forest in New Zealand’s North Island. Young Ishikawa spent about a month and a half on his own here, documenting his stay. ©︎NAOKI ISHIKAWA

カヌーの原材料となる木「カウリ」。ニュージーランドの北島だけに生育する針葉樹で、屋久杉を超える大きさの樹齢2500年を数える巨木もある。©︎NAOKI ISHIKAWA

The “Kauri”, a coniferous tree found only on New Zealand’s North Island, was used for canoe building. The largest trees are over 2500 years old and are bigger than the Yakusugi in Japan. ©︎NAOKI ISHIKAWA

森を歩いていると、突如と開けて、間欠泉や温泉の湧く池が現れることも。硫黄や酸性が強く、入浴はできないそう。立ち昇る煙や、オレンジに変色した岩が、この森固有の風景をつくっている。©︎NAOKI ISHIKAWA

Walking in the forest, sometimes a clearing will suddenly appear, revealing a geyser or a lake with a natural hot spring. The high levels of sulfur and acid make them unsuitable for bathing. Smoke rises into the air and the rocks have been tainted orange, creating one of the unique landscapes to be found in the forest. ©︎NAOKI ISHIKAWA

ひとつの森を通して、世界の森を見る。

――森と対峙しながら、石川さんはどんなことを感じていたのでしょうか?

植物以外は何もないのに、とても満たされているような感覚がありました。生命の気配が充満していて、その一方で、どこか真空のような“無”も感じる。「VOID」とは「空間」「無限」「すき間」といった意味で、この矛盾した感覚を表しています。

もうひとつ考えていたのは「ひとつの森はすべての森、すべての森はひとつの森」ということでした。滞在中はたっぷりと時間があるので、地を這う蟻や、植物の葉脈をぼーっと眺めたりもするんです。すると、マクロとミクロが交差していく。遠近感が逆になるというか、小さな世界の中に、大きな世界が見えてくるんです。そうした体験を率直に言い表したのが、「ひとつの森はすべての森、すべての森はひとつの森」ということです。なにも世界を知るために、世界のすべてを見る必要はないし、ひとつを見続けた先に全体を理解することもある。

マオリの森に滞在している間は、そんなことを感じたり考えたりしていました。

One forest as a lens to all the forests of the world.

――What did you feel as you stood face to face with the forest?

Even though I was surrounded by nothing other than plants, I had a feeling of great fulfillment. There was an abundance of life, but at the same time I could also feel a sort of vacuum or “void”. Void means “space” or “gap” or “infinity”, thus aptly capturing these contradictory sensations.

Another thought I had was “one forest is all forests; all forests are one forest”. As I had an abundance of time during my stay in the forest, I would sometimes sit and watch ants walking on the ground, or absent-mindedly stare at leaf veins on plants. When doing so I found that the macro and the micro would intersect. It was as if the perspective had been reversed and I started to see the larger world inside the smaller world. The phrase: “One forest is all forests; all forests are one forest” is a simple and honest description of this experience. There’s no need to see the whole world in order to know the whole world; sometimes continuing to look at one single thing can lead to an understanding of the whole.

These are the sorts of feelings and thoughts I had during my stay in the Maori forest.

and wander 丸の内に展示された「THE VOID」シリーズ。大判のプリント4点が並ぶ。カウリの森に入り込んだような没入感を味わってほしい。

and wander Marunouchi, here we have exhibited four large prints from the original “THE VOID” photography series. It’s our hope that these large prints give you the feeling of being immersed into the deep native New Zealand forest in which they were taken.

and wanderの定番「CORDURA Typewriter Shirt Series」に石川さんの写真をプリントしたコラボアイテム。50年以上に渡り高機能繊維を作り続ける革新的なファブリックメーカーCORDURA®の生地で、耐久性があり、経年変化を楽しみながら、長く愛用できる。

NAOKI ISHIKAWA THE VOID CORDURA shirt / SEA ¥35,200(税込)

Collaboration item - and wander classic, the “CORDURA Typewriter Shirt Series” printed with a photograph by Ishikawa. CORDURA® have been making advanced fabric for over 50 years, CORDURA® fabric is highly durable, and this item is sure to become a long-lasting favorite.

NAOKI ISHIKAWA THE VOID CORDURA shirt / SEA ¥35,200 (tax included)

背には“ONE FOREST IS ALL FORESTS”という石川さんの言葉が。カラーはホワイトとブラックの2種。コラボアイテムの売り上げの一部は、ニュージーランドの森林保護団体へ寄付される。

NAOKI ISHIKAWA THE VOID CORDURA shirt / TREE ¥35,200(税込)

Printed on the back of this shirt is Ishikawa's powerful phrase, "ONE FOREST IS ALL FORESTS". The shirt is available in two colors, white and black. A portion of the proceeds from the sale of the collaborative items will be donated to a forest protection organization in New Zealand.

NAOKI ISHIKAWA THE VOID CORDURA shirt / TREE ¥35,200(tax included)

マオリの人々から学ぶ、人と自然の真の共生。

――マオリの人々との交流で印象に残っていることはありますか?

ニュージーランドは白人が暮らす国というイメージがあるかもしれませんが、元々島にはマオリの人々がいて、彼らはポリネシアの言葉を話していました。島の名も「ニュージーランド」ではなく、「アオテアロア(白く長い雲がたなびく地)」という現地名があります。彼らから島の歴史やスターナビゲーションの話を聞くことで、ここはポリネシア文化の西の端なんだと、改めて認識しました。

そして、彼らの森との関わり方にも多くを学びました。彼らは「森に生かされている」ということを、綺麗事ではなく実感している。今では“共生”という言葉も手垢のついたものになってしまいましたが、真の意味で自然と共に生きているんです。

Learning about true coexistence with nature from the Maori.

――Did anything in particular leave a lasting impression on you from your exchanges with the Maori?

Although our image of New Zealand might be of a country inhabited by Caucasians, it was actually originally inhabited by the Maori people. The Maori spoke Polynesian and the islands have the Maori-language name of “Aotearoa” (long white clouds). Listening to the Maori recounting the history of the islands and explaining star navigation, I was reminded that “Aotearoa” is the western edge of the Polynesian cultural region.

I also learned a lot from the way they interact with the forest. They sincerely believe that “the forest gives them life”. Nowadays the word “coexist” has become hackneyed, but the Maori live with the forest in the truest sense of the word.

写真に写る白い葉は「シルバーファーン」と呼ばれ、マオリの人々が森で迷わないために道しるべとして置いたもの。後から来た仲間に行き先を伝えるために置くこともある。

The white leaf pictured is called the “silver fern”. The Maori use it to mark their way so as not to get lost in the forest. They also sometimes leave them as a guide to the people following after them.

――マオリの人々には森を「守る」という意識はないのですね。

マオリだけではなくて、ヒマラヤのシェルパも、北極のイヌイットも、自然の一番近くで生きている彼らには「守る」という感覚とはちょっと違う敬意や畏怖の念を抱いて生きている。自然を守る、という視点を掲げているのは、むしろ日本や欧米といった先進国ではないでしょうか。

僕自身、自然保護という言葉がいつも引っかかっていたんです。自然の方が圧倒的に人より強くて、人はそれによって生かされているのに、どうして自然より優位に立っているような表現になるのだろう、と。

『THE VOID』に写る原生林は、マオリという森のよき理解者によって、その姿が保たれてきました。決して、人が足を踏み入れない手つかずの森ではないのです。敬う気持ちや畏れを持って関わることで、人と自然はよき関係を結ぶことができるのではないか。

この展示が、そんなことを考えるきっかけになれば嬉しいです。

――The Maori do not believe in “protecting” the forest.

The people living closest to nature - not just the Maori, but also the Sherpa in the Himalayas and the Inuit in the Arctic, live with a certain reverence and awe for nature that is somewhat different to the notion of “protecting” it. I think it is more developed countries such as Japan or western nations that have come up with the notion of protecting nature.

Personally, something about the phrase “protecting nature” has always bothered me. Protecting nature implies that humans dominate over the natural world, but in reality, nature is overwhelmingly stronger than the human race, and nature is the giver of life, not the other way around.

The virgin forests featured in “THE VOID” have been preserved by the Maori people and their deep understanding of the forest. They are certainly not “untouched” places in which man never sets foot. Could it be that by basing our interactions with nature on reverence and awe, mankind can build a genuine relationship with the natural world?

We hope that this exhibition will be an opportunity for people to ponder such notions.

PROFILE

石川直樹

1977年東京生まれ。写真家。東京芸術大学大学院美術研究科博士後期課程修了。人類学、民俗学などの領域に関心を持ち、辺境から都市まであらゆる場所を旅しながら、作品を発表し続けている。2008年『NEW DIMENSION』(赤々舎)、『POLAR』(リトルモア)により日本写真協会賞新人賞、講談社出版文化賞。2011年『CORONA』(青土社)により土門拳賞を受賞。2020年『EVEREST』(CCCメディアハウス)、『まれびと』(小学館)により写真協会賞作家賞を受賞。著書に、開高健ノンフィクション賞を受賞した『最後の冒険家』(集英社)ほか多数。コロナ禍の渋谷と人のいなくなった街で繁殖するネズミの世界を写した『STREETS ARE MINE』(大和書房)や、香川県の屋外飛び込み台で飛び込み練習をする青少年を写した『MOMENTUM』(青土社)など、近年の活動にも注目が集まる。

http://www.straightree.com/Naoki Ishikawa

Photographer. Naoki Ishikawa was born in Tokyo in 1977 and completed a latter doctoral program at the Graduate School of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. Interested in anthropology and ethnology, he has traveled widely, visiting every kind of environment, from urban to remote regions, creating outstanding works along the way. In 2008, he received the New Photographer Award from the Photographic Society of Japan and the Kodansha Publication Culture Award for Photography for “NEW DIMENSION” (AKAAKA Art Publishing Inc.) and “POLAR” (Little More). In 2011, he received the Domon Ken Award for “CORONA” (Seidosha) and in 2020 he received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Photographic Society of Japan for “EVEREST” (CCC Media House) and “MAREBITO” (Shogakukan Inc.). He has also written numerous books, including “The Last Adventurer” (Shueisha Inc.) for which he received the Kaiko Takeshi Non-Fiction Award. His latest publications are also garnering acclaim, and include “STREETS ARE MINE” (Daiwashobo Co., Ltd.), which depicts Shibuya during the COVID-19 pandemic and a world where rats multiply in urban spaces abandoned by people, and “MOMENTUM” (Seidosha), which depicts youths diving off an outdoor diving platform in Kagawa prefecture.

http://www.straightree.com/edit PAPERSKY

text Yuka Uchida

photography Machiko Fukuda (exhibition & collaboration item photo)

translation Yuko Caroline Omura